Marine Life Society of South Australia Inc.

2005

Journal

NUMBER 15

CONTENTS

On Some

South Australian Caulerpa Species

Preliminary

Field Observations of Mating and Spawning in the Squid

Sepioteuthis australis

More Nudibranch Discoveries

Recent Requests to Our Society for Information

Further Recent Requests to Our Society for

Information

EDITORIAL

- Philip Hall

Welcome

to the 2005 edition of the MLSSA Journal. As usual this replaces the December

monthly Newsletter.

This

edition of the Journal starts with an article containing a somewhat

controversial view of the benefits of Caulerpa taxifolia by MLSSA member

Brian Brock.

The

third and final part of the squid series of articles we have printed over the

past two years by Troy Jantzen and Jon Havenhand follows.

Steve

Reynolds contributes a beautifully illustrated article on local nudibranchs and

follows with an article on information requests received by the Society.

I

have added a second part to the information requests with some that I have answered.

DISCLAIMER

The

opinions expressed by authors of material published in this Journal are not

necessarily those of the Society.

EDITING: Philip

Hall

PRINTING: Phill

McPeake

CONTRIBUTORS: Brian

Brock

Troy

Jantzen &

Jon

Havenhand

Steve

Reynolds

Philip

Hall

PHOTOGRAPHY: Dennis

Hutson

Yoshi

Hirano

Philip

Hall

On Some South Australian Caulerpa Species

by B. J.

Brock BSc, Dip Sec Ed, MSc,

FRSSA, MAI Biol

The genus

Caulerpa includes a large number of bright green stoloniferous algae

bearing erect axes from which small side-branches called ramuli arise. The size, shape and arrangement of the ramuli on the axes, aids in

the identification of the species. Fine root-like structures called

rhizoids attach the stolons to the substrate. In some species, the primary axis

branches and the branches also have ramuli on them. Refer to Womersley’s habit

photographs and drawings of ramuli, and descriptions etc. if you wish to try

your hand at keying out species (Womersley H. B. S.; 1984, pp. 253-274)

Drift

specimens of Caulerpa may be found on many of our beaches after storms.

Shepherd and Womersley (1970) record summer shedding of fronds of two Caulerpa

species, leaving persistent stolons. Some species may be found attached in

Intertidal pools or in the upper sub-littoral. A few species occur over a

considerable range of depths. Caulerpa cactoides is a fairly robust

species with clavate ramuli. Fragments of it are quite often washed up after

storms, and I have seen it growing in several places in the upper sub-littoral

zone (Port Douglas near Coffin Bay, Marion Bay, Groper Bay near Pondalowie,

Marino Rocks, Edithburgh) and thought of it as a fairly shallow-water species.

However, systematic collecting on the Nuyts Archipelago found it in the 32-38

metre zone and also at 2 metres in a sheltered site (See: Shepherd S. A. and

Womersley H. B. S., 1976, p.188). Lucas (1936) p.48 records it “from low water

mark to a depth of several fathoms”.

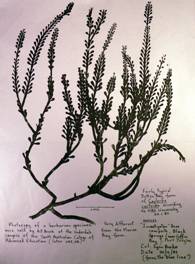

The Port

Douglas form of Caulerpa cactoides differs from the Marion Bay form. One

illustration accompanying this article is a photo-copy of a herbarium sheet

prepared from a specimen collected from the blue-line off the Investigator Base

Campsite near Black Springs (ANZSES Expedition) by Lynn Brake on 30/12/83.

Picture 1

Port Douglas form

of C. cactoides

Compare it

with the Marion Bay form.

Picture 2

Robust Marion Bay

form of C. cactoides

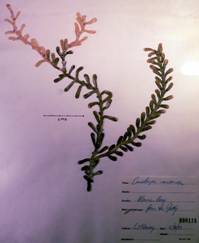

Another species with a wide range of

depth distribution is Caulerpa scalpelliformis. The scuba divers

collected it on the four different transects in the St Francis group of islands

at depths from 2-35 metres (Shepherd and Womersley 1976). I found it upper

sub-littoral at the base of calcareous and harder metamorphic rocks near the

Black Springs base camp. In this situation, it had to tolerate underwater

sandstorms when there was much wave action. It could be confused with C.

taxifolia but the ramuli in C. taxifolia are in opposite pairs (see

Pic 3) while those of C. scalpelliformis alternate along the axis. The

shapes of the ramuli also differ slightly in the two species. Refer to the West

Island, Pearson Island and St Francis papers for accounts of algal ecology.

Picture 3

C.

taxifolia from Angas Inlet.

Ramuli in

opposite pairs on erect fronds.

Caulerpa trifaria

is a fairly delicate Caulerpa species that used to be popular in

marine aquaria. Three rows of fine ramuli run up the erect axes. The photo (Pic

4) shows the habit of a specimen collected at West Beach in 1975 by my

daughter. Fresh drift specimens of marine algae can be rinsed in fresh water

and floated out on cartridge paper. Dry between newspapers under weight. Muslin

over the specimen will prevent it from sticking to the newspaper, but papers

must be changed frequently to avoid mildew. Some dry reds are beautiful (Pic 5)

and keep for years, especially if stored in a cool, dry, dark place.

Picture 4

C. trifaria has

three rows of fine ramuli.

Picture 5

A herbarium sheet

of the lovely red alga Kallymenia tasmanica

Caulerpa

taxifolia (Aquarium Weed), is the species that initiated the battle

to contain it in West Lakes. That battle has been lost. Like Barley Grass and

other weeds on land, I think we will have to learn to live with it (and be

thankful that it is a photosynthetic organism that fixes a lot of solar energy

that passes on down whatever food chains). Some time ago, I saw what I thought

might be Caulerpa taxifolia growing near an old dead mangrove tree lying

near the end of the Fishermen’s jetty in the Angas Inlet. On 8/8/05, I decided

to check it out more closely, from the shore. It had gone, but just around the

corner, in a small inlet, was a knee-deep patch of suspicious-looking weed. I

know this inlet well because I used to find the upside-down jellyfish

Cassiopea ndrosia (Plates 15,3 and 15,4 of

Shepherd and Thomas 1982) here in thousands before the blooms of red tide

organisms began. The floor of the little inlet, used to be bare of weeds. A

sample of the weed-patch proved it to be a mix of Caulerpa taxifolia and

a recently introduced Western Australian species called Caulerpa racemosa (see

p. 270 and fig 91B of Womersley H. B. S. 1984; also the photo Pic 6

P 10 accompanying this article). I believe a similar mixed crop of weeds

is found along the Port River side of Torrens Island. This is not surprising

considering the way water circulates around Garden Island on the ebb and flow

of the tides. (Cold water from North Arm is used for cooling purposes by the

Torrens Island Power Station.) North Arm and Torrens Island are connected by a

causeway that separates the cold North Arm waters from the warm effluent

discharged into Angas Inlet. In times of peak demand, remote sensing of surface

water temperature (Thomas et al. 1986 fig.4) shows that some of the warm

effluent completely circles Garden Island. The warm effluent affects the

distribution and abundance (Thomas I. M. et al., 1986) and seasons of

settlement (Brock B. J. Unpublished M.Sc. thesis; and 1985) of some marine

invertebrate species.

I collected Caulerpa racemosa and an Ulva

species from the upper sublittoral in a mooring basin at the junction of

the Port River and North Arm (near the open air produce market) on 24/3/04. I

was able to key out the Caulerpa as C. racemosa using Womersley

(1984). Bob Baldock of the State Herbarium, verified

my identification on 26/3/04 and told me he had seen it on a collecting panel

about 1½ years previously. I mounted my specimen for the Maritime Museum’s

Dolphin display. Steve Reynolds of the Marine Life Society of South Australia

picked the herbarium sheets and drawings up on 2/4/04. Bob and I went to Angas Inlet, and the North Arm/Port River site on 5/4/04 for more

specimens of C. racemosa for the State Herbarium. We found plenty in

Angas Inlet from the Postal Institute’s boat ramp, to the end of the

Fishermen’s jetty (east of the public boatramp).

I have

found Bugula neritina growing on an old Caulerpa racemosa ramulus,

and three young colonies of an encrusting bryozoan (probably Celleporaria

cristata; see Gordon D. P. 1989 p33 and plate 16, D-F) on a Caulerpa

racemosa stolon. An older colony of what was probably the same encrusting bryozoan, was found on sea lettuce (Ulva sp.). Shepherd and

Thomas (1982) Plate 28,4 is of a mature live colony.

So, like

the European feather-duster worm, Caulerpa racemosa provides a stable

substrate for other marine benthic organisms in a zone otherwise denuded of

marine macrophytes (perhaps because of high nitrogen levels; see Neverauskas

1988; and presentations at the Friends of Gulf St Vincent forum held at SARDI

Hamra Road on 22/10/05).

Close examination of a specimen of Caulerpa

taxifolia from Angas Inlet (8/8/05) revealed the presence of many different

phyla of marine invertebrates. Terebellids and other segmented worms,

Amphipods, a brittle star, a seasquirt on a stolon, numerous silt tubes

probably inhabited by crustaceans (Amphipods) and Isopods. The angle between

main fronds and branches provided a microhabitat for many of the silt tubes.

Rhizoids looked as if they would also provide a microhabitat for invertebrates

(and many microorganisms). A knee-deep crop of C. taxifolia is likely to

be far more productive than a “bare” area on which marine flowering plants have

been killed off by other factors in a polluted environment. I say “bare”

because I am well aware that there are microscopic photosynthetic and

chemosynthetic organisms that can fix a lot of energy in these areas. I cannot

comment on whether C. taxifolia can invade a healthy area of marine

flowering plants not debilitated by polluting factors. We might be lucky to

have C. taxifolia, just as many of our Arid Zone graziers feel lucky to

have weeds like Barley Grass, Salvation Jane and Wards Weed (Carrichtera

annua) stabilizing soils long-since denuded of native species by

overgrazing. It is time to look at positive aspects of C. taxifolia.

Picture 6

C. racemosa recently

found in the Port River and Angas Inlet

REFERENCES

Brock B.

J. (1979) Biology of Bryozoa Involved in Fouling at Outer Harbour and Angas

Inlet. Unpublished M.Sc. Thesis University of Adelaide

Zoology Dept.

Brock B.

J. (1985) South Australian fouling Bryozoans. In Nielsen C.

and Larwood G. P. (Eds.) Bryozoa: Ordovicion to

Recent. (Olsen & Olsen) p.p. 45-49.

Gordon D.

P. (1989) The Marine Fauna of New Zealand: Bryozoa:

Gymnolaemata (Cheilostomata Ascophorina)

from the Western South Island Continental Shelf and Slope. New Zealand

Oceanographic Institute Memoir 95 plate 16, D.E.F., Celleporaria cristata.

Lucas A.

H. S. (1936) The Seaweeds of South Australia. Govt. Printer Adelaide.

Neverauskas V. P. (1988) Accumulation of periphyton on artificial substrata

near sewage sludge outfalls at Glenelg and Port Adelaide, South Australia. Trans.

R. Soc. S.Aust. 112 (4) p.p. 175-177.

Shepherd

S. A. and Thomas I. M. (1982) Marine Invertebrates of Southern Australia Part 1

Plates 15,3 and 15,4 for Cassiopea ndrosia, and

28,4 for mature live Celleporaria cristata.

Shepherd

S. A. and Womersley H. B. S. (1970) The sublittoral

ecology of West Island, South Australia 1. Environmental

Features and the Algal Ecology. Trans. R. Soc. S.

Aust. 94 p.p. 105-138.

Shepherd

S. A. and Womersley H. B. S. (1971) Pearson Island Expedition 1969.-7. The Subtidal Ecology of Benthic Algae. Trans.

R. Soc. S. Aust. 95 (3) p.p.155-167.

The other

parts were: 1. Narrative 2. Geomorphology 3. Contributions to the Land Flora 4. The

Pearson Island Wallaby 5. Reptiles 6. Birds 7. Helminths

Shepherd

S. A. and Womersley H. B. S. (1976) The subtidal algal

and seagrass ecology of St Francis Island, South Australia. Trans.

R. Soc. S. Aust. 100 (4) p.p.177-191.

Thomas I.

M. et al (1986) The effects of cooling water discharge

on the intertidal fauna in the Port River estuary, South Australia. Trans. R.

Soc. S. Aust. 110 (4) p.p. 159-172.

Womersley H. B. S. (1984) The Marine Benthic Flora of Southern Australia. Part 1. (Govt. Printer, Adelaide). Caulerpa spp., p.p. 253-274.

Preliminary Field Observations of Mating and Spawning

in the Squid Sepioteuthis australis

TROY

M. JANTZEN* AND JON N. HAVENHAND#

School

of Biological Sciences, Flinders University,

GPO

Box 2100, Adelaide, South Australia, 5001

*

To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: Troy.Jantzen@

bms.com

#

Current address: Tjämö Marine Biological Laboratory, Göteborg University, 452 96 Strömstad,

Sweden.

Received

15 February 2002; accepted 31 January 2003.

Reference:

Biol. Bul. 204:290 - 304 (June 2003)

C 2003

Marine Biological Laboratory

Sepioteuthis australis is a moderately large (≈30 cm mantle length) teuthoid squid, common throughout the coastal waters of

southern Australia and New Zealand (Mangold and

Clarke, 1998). Although prevalent throughout this region, no observations of

copulation have been reported for this species, and spawning behavior has been

reported only once in situ [as S. bilineata (Larcombe and Russell, 1971, see Mangold and Clarke, 1998)].

The object of the present note is to contribute to the knowledge of mating

and spawning behavior of S. australis. The observations

described here are the result of preliminary observations at the latter stages

of the spawning period of this little-studied species. We provide a brief

overview of S. australis mating and spawning behavior in the field, together

with an insight into the proposed research that will be conducted on this

species in future spawning seasons.

Materials and Methods

Throughout summer, S. australis move inshore to spawn, frequently

utilizing the same spawning grounds each year (unpubl.

observ.). Observations of S. australis reported

here were obtained from a spawning ground approximately 20-40 m offshore (from

the low tide mark) from the suburb of Marino, South Australia (130°30'E,

38°02'S). The benthos in this area consists of seagrass (Amphibolis

antarctica) and brown

macroalgae (Sargassum spp.) interspersed with

patches of bare sand and rock, and extends for several kilometers along the

coastline in this manner. The site at Marino is one of several spawning sites

for S. australis along this stretch of coastline, all of which share

these benthic characteristics.

During the spawning season, S. australis lay eggs in clusters

consisting of numerous egg capsules (approximately 300 capsules per cluster;

Larcombe and Russell, 1971), with each capsule containing 3-6 eggs. These egg

clusters are commonly found attached to the thalli of

the brown macroalgae Sargassum spp. This genus

of macroalgae is also used as an egg deposition site for other squid species

such as S. lessoniana (Segawa, 1987).

A total of nearly 4 h of ad libitum sampling

(Martin and Bateson, 1993) were made over a 3 d

period by SCUBA and snorkeling. Water depth on the spawning ground varied

between 2-4 m depending on the tide. Squid behavior throughout the observation

period was photographed with a Nikonos V camera. Attempts to record mating and

spawning behavior using a Canon E850-Hi video camera in waterproof housing were

unsuccessful due to an error with the tracking system on the camera. As a

result, valuable ‘one-zero’ sampling (Martin and Bateson,

1993) data of mating and spawning could be analyzed. Furthermore, body

patterning of the adults with each behavior could not be classified.

Results and Discussion

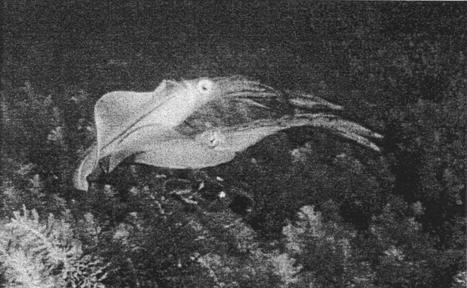

Egg Laying and Agonistic Behavior.—Larcombe and

Russell (1971) documented the behavior of six adult S. australis (two

male, four female) as the females attached egg capsules to an egg cluster that

had detached from its normal habitat and had become entangled in an artificial

reef. In contrast, the observations reported here describe spawning by

numerous individuals on egg clusters attached to Sargassum spp.

Sex ratio on the spawning ground was male biased. Although quantitative

measurements of the specific number of males and females in view at any one

time were not obtainable from the video footage, direct observation showed that

all females were paired with a male while several unpaired males swam amongst

the paired individuals. These unpaired males were observed attempting to

displace paired males from their mate: a behavior that was met with fierce

agonistic responses from the paired male who would endeavor to remain between

the female and the competitor using his mantle and fins. Agonistic behavior

often escalated into a fight with both males extending their arms and tentacles

and colliding into each other (Fig. 1). If the unpaired male did not withdraw,

a swimming fight would result, and the two males rapidly swam out of visible

range while continually colliding in this manner. ‘Swimming fights’ left the

female unattended and subject to pairing with other competitive males. Although

this behavior appears detrimental to the paired male, it may be advantageous to

the female, and a similar behavior has been observed in the cuttlefish Sepia

apama where females engage in extra pair copulations while a guarding male

is preoccupied with fighting with a competitor (R. T. Hanlon pers. comm.,

2000).

Figure 1. Two males fighting. The paired male (bottom) is

using his body

and fins to

‘guard’ his mate (background) from the advances of an

unpaired male (top).

In one instance, rather than a ‘swimming fight’, agonistic behavior

escalated to physical combat (DiMarco and Hanlon, 1997) and a paired male was

seen wrapping his tentacles and arms completely around the mid-mantle region

of an unpaired male. This behavior has also previously been observed in fights

among S. apama and is assumed to be an attempt to bite the intruder (R.

T. Hanlon pers. comm., 2000). Like the response of the unpaired males in the S.

apama fights, the unpaired S. australis male immediately jetted

away.

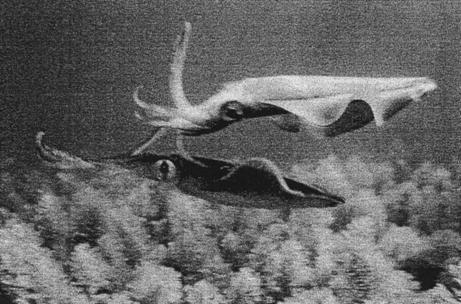

As well as defending their female from other males by fighting, paired

males guarded the female while she laid eggs. ‘Mate-guarding’ (sensu Sauer et al., 1992; Hanlon and Messenger, 1996)

involved the male remaining a few centimeters above his mate while she attached

egg capsules to a cluster (Fig. 2). Immediately following egg-laying, the pair

moved backwards away from the egg cluster and began a ‘mutual-rocking’ behavior

(Moynihan and Rodaniche, 1982; Hanlon and Messenger, 1996) in which the pair

swam side-by-side in a slow and deliberate forward and back motion. This

behavior stopped when the female approached the egg cluster and deposited a new

capsule amongst it in the same manner as that described by Larcombe and Russell

(1971).

guarding a female.jpg)

Figure 2. Male (top) guarding a female (below) as she prepares to add

a new egg

capsule to a cluster (not visible in photo). Broken

spermatophores from a previous mating attempt (successful mating

results in spermatophores being deposited in the buccal region of the

receptive female) can be seen on the dorsal surface of the female.

Egg laying behavior of squid in spawning aggregations has been observed in

numerous species congregating around a large, central, relatively exposed,

communal egg cluster (Griswold and Prezioso, 1981; Sauer et al., 1992; Segawa

et al., 1993; Hanlon et al, 1994; 1997; Hanlon and Messenger, 1996). In our

observations of S. australis spawning, no more than three paired females

were seen laying eggs in the same egg cluster. Furthermore, although common in

some squid species (Hanlon and Messenger, 1996), no distinctive ‘zones’ of

mating and spawning activity could be identified for S. australis throughout

the observational period. It is possible that further observation will clarify

this issue.

Copulation Behavior of Paired Males.—Copulation in

Sepioteuthis involves the male depositing spermatophores into either the mantle

cavity when the male approaches from below the receptive female (Segawa, 1987;

Segawa et al., 1993), or onto the arm region when the

male approaches from beside or above the female (Moynihan and Rodaniche, 1982;

Boal and Gonzalez, 1998). When spermatophores are placed on the female arm

region, the male does so in one of two ways: in reports of S. sepioidea mating

in the field, the male positions himself next to, or ahead of the female, turns

towards her, and ‘strikes’ the female on the ‘forehead’. Alternatively, reports

of S. lessoniana mating in the laboratory describe a mating position in

which the male ‘flips’ upside-down to deposit spermatophores on the head or

arms of the female (Boal and Gonzalez, 1998). It is this latter ‘male-upturned’

mating position that was observed by paired males of S. australis in the

field.

Mating with the male in the upturned position was observed on six

occasions, each of which occurred prior to egg laying by the female while the

spawning pair was in close proximity to the egg cluster (usually <1.5 m).

Boal and Gonzalez (1998) categorized the male-upturned mating behavior of S.

lessoniana into four distinct behaviors, of which only three were observed

here: ‘pre-mating behavior’, ‘flip’, and ‘contact’; the fourth (‘attempt’) not

being observed in S. australis.

S. australis still displayed some behavioral traits consistent with S.

sepioidea mating in the field (Moynihan and Rodaniche, 1982). Unlike

‘pre-mating’ behavior in S. lessoniana that involved rapid back and

forth swimming by the mating pair (Boal and Gonzalez, 1998), ‘mutual-rocking’

in S. australis was slow and deliberate, similar to that described for S.

sepioidea (Moynihan and Rodaniche, 1982). Immediately prior to mating, male

S. australis were observed to fold back one tentacle horizontally toward

the female for a few seconds, such that the suckers on the club of the male

faced toward the female, a behavior that may be unique to S. australis mating.

The purpose of this ‘club display’ behavior remains unclear,

however it may signal the male's intention to mate with the female.

Following the male ‘club display’ to the female, the male was observed to

move directly above, or slightly anterior to, the body

of the female. The male then swiftly rotated 180° around the longitudinal axis

to achieve an inverted position above the female. This ‘flip’ action was

observed in males positioned both alongside as well as above the female in S.

lessoniana (Boal and Gonzalez, 1998). However, in S. australis it

occurred when the male was above the female.

While inverted, the male reached down with an arm and made cont with the

buccal area of the female (Fig. 3). From our observations we were unable to

determine if mating in this manner was successful. Unlike S. lessoniana in

which mating ended with the female rapidly jetting away (Boal and Gonzalez,

1998), ‘contact’ in S. australis was terminated when the male returned

to his original position alongside the female, similar to the post-mating

behavior described for S. sepioidea (Moynihan and Rodaniche, 1982). In S.

sepioidea spermatophores are visible on the hectocotlyus of the male prior

to mating (Arnold, 1965). This was not the case for the mating behavior

described here and the only spermatophores observed were those affixed to the

dorsal mantle of a female (Fig. 2). It is assumed that a male placed these spermatophores

there in an unsuccessful mating attempt, although the behavior that resulted in

that placement was not observed.

Figure 3. Lateral view of the male upturned mating position. The male

(top) can be seen in an upside down position

reaching down in an attempt

to deposit

spermatophores in the buccal region of the female (below).

Extra-pair Copulations.—As well as ‘male-upturned’ mating by paired males, behavior

consistent with extra-pair copulations in other species was observed by

unpaired S. australis males. In Loligo

pealei and L. vulgaris reynaudii,

extra-pair copulations occur by ‘sneaker males’ mating with females both at the

large communal egg mass, and at a short distance from the egg mass (the

‘mating/sneaker zone’; Hanlon, 1996; Hanlon and Messenger, 1996; Hanlon et al.,

in press). All of the extra-pair copulations that were observed in S.

australis occurred as a female added a new egg capsule to an egg cluster.

While laying eggs, the depth of the algal canopy was such that only the

mantle tip of the female protruded above the algae. Therefore, males guarding a

mate were always positioned some distance above the substratum either

immediately above or beside the female. Unpaired males were observed to swim

rapidly toward the female from the side or behind, dart amongst the Sargassum

and make physical contact with the female before quickly jetting away. The

nature of this contact was similar to the ‘sneaker’ mating observed in L.

pealei (Hanlon et al., 1994).

‘Sneaker’ mating by an unpaired male was identified once throughout the

observational period, while at least two other encounters showed aspects of

sneaking mating. In the first instance, an unpaired male made contact with the

arms of a female which was visibly laying eggs in a cluster. This behavior

occurred very rapidly such that it was not possible to determine if mating was successful, and (if so) where the spermatophores were

deposited. On two further occasions a male was seen disappearing into the algal

canopy within 0.5 m of a female laying eggs, soon

afterward reappearing and quickly jetting away. In these cases the head of the

female was almost completely obscured from view by the Sargassum and no

copulation was seen. However, behavior of the unpaired male in these latter two

instances was identical to that seen in the previously described encounter.

Figure 4. Unpaired male (left) attempting to displace another male (middle)

from his mate (right). The two males have tentacles and arms out-stretched

in a sign

of agonistic behavior. In the bottom left comer, an empty egg

capsule is noticeable.

Empty Egg Capsules.—Egg capsules were attached to the top of the Sargassum in

the spawning area on each day of observation (Fig. 4). Closer examination

revealed that these egg capsules did not contain any eggs. Furthermore, these

capsules were absent in the week following the spawning event (although

numerous egg clusters remained present). The purpose of these empty capsules is

not clear, however at least two possible functions can be speculated: (1)

locational ‘markers’: given our observations of repeated egg laying on

established egg clusters, the migration to and from these clusters during the

‘mutual-rocking’, and the dense algal canopy which frequently obscured egg

clusters from view, these empty capsules may flag the position of egg clusters,

facilitating their location by adults. (2) Capsules act as spawning stimulants:

as egg capsules have been demonstrated to induce male agonistic behaviour in

laboratory trials of L. pealeii (King et al.,

1999), and promote spawning in L. pealii (Arnold, 1962) and Loligo opalescens (Hurley,

1977), egg capsules (empty or full) may stimulate spawning of adults entering

the area. The reason for this may be visual or, as recent studies have suggested,

may be a response to a chemical or tactile stimulus embedded in the egg

capsules (King et al., 1999). Further studies are required to verify these

hypotheses.

conclusions

Observations of a natural spawning aggregation of

approximately 40 S. australis in South Australia have revealed several

previously undescribed aspects of spawning behavior

in this species. Male S. australis repeatedly copulated in the

‘male-upturned’ position and engage in behavior similar to extra-pair

copulations that are reported for other squid species. Further research is

being conducted in an attempt to determine the precise nature of these

behavioral traits. Focal animal sampling of fighting, mating and spawning

behavior using a digital camera will enable specific body patterning of each

sex to be analyzed. Continuous recording of the focal animal(s) will also

identify duration of spawning and mating, time between these events, and the

frequency and characteristics of extra-pair copulations. In addition, empty egg

capsules, which may serve as locational markers and/or spawning stimulants,

were observed deposited on the distal fronds of macroalgae within the spawning

area Laboratory and field studies will investigate this unusual behavior.

acknowledgments

We are thankful to L. van Camp for comments on this

research, and to B. Lock, A. Mack, and A. Hirst for

help SCUBA diving and snorkeling in the field.

literature cited

Arnold, J. M. 1962. Mating behavior and social structure

in Loligo pealii. Biol. Bull.

123: 53-57.

______. 1965. Observations on the mating behavior of the squid Sepioteuthis

sepioidea. Bull. Mar.Sci. 15:216-222.

Boal, J. G. and S. A. Gonzalez. 1998.

Social behaviour of individual oval squids (Cephalopoda,

Teuthoidea, Loliginidae,

Sepioteuthis lessoniana) within a captive school. Ethology

104: 161-178.

DiMarco, F. P. and R. T. Hanlon. 1997.

Agonistic behavior in the squid Loligo plei (Loliginidae, Teuthoidea): Fighting tactics and the effects of size and

resource value. Ethology 103: 89-108.

Griswold, C. A. and J. Prezioso. 1981. In

situ observations on reproductive behaviour of the long-finned squid, Loligo pealei. Fish.

Bull. U.S. 78: 945-947.

Hanlon, R.T., M. J. Smale and

W. H. H. Sauer. (in press). The mating system

of the squid Loligo vulgaris

reynaudii (Cephalopoda,

Mollusca) off South Africa: fighting, guarding,

sneaking, mating and egg laying behavior. Bull. Mar. Sci.

_______. 1996. Evolutionary games that squids play: Fighting, courting,

sneaking, and mating

behaviors

used for sexual selection in Loligo pealei.

Biol. Bull. 191: 309-310.

_______ and J. B. Messenger. 1996. Cephalopod

behaviour. Cambridge Univ. Press. Cambridge.

______, M. J. Smale and W. H.

H. Sauer. 1994. An ethogram of body

patterning behavior in the squid Loligo vulgaris reynaudii on the spawning

grounds in South Africa. Biol. Bull. 187:363-372.

______, M. R. Maxwell and N. Shashar. 1997. Behavioral dynamics that

would lead to multiple paternity within egg capsules of the squid Loligo pealei. Biol. Bull. 193: 212-214.

Hurley, A. C. 1977. Mating behavior of

the squid Loligo opalescens.

Mar. Behav. Physiol. 4:

195-203.

King, A. J., S. A. Adamo and R. T. Hanlon. 1999. Contact

with squid egg capsules increases agonistic behavior in male squid (Loligo pealeii). Biol. Bull.

197: 256-258.

Larcombe, M. F. and B. C. Russell. 1971.

Egg laying behaviour of the broad squid, Sepioteuthis bilineata.

NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 5:3-11.

Mangold, K. and M. R. Clarke. 1998. Subclass Coleoidea. Pages 499-563 in P. L. Beesley, G.

J. B. Ross, and A. Wells, eds. Mollusca: The southern

synthesis. Fauna of Australia. CSIRO Publishing,

Melbourne.

Martin, P. and P. Bateson. 1993. Measuring Behaviour: An

Introductory Guide. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

Moynihan, M. and A. F. Rodaniche. 1982.

The behavior and natural history of the Carribean

reef squid Sepioteuthis sepioidea. With a

consideration of social, signal, and defensive patterns for difficult and

dangerous environments. Adv. Ethology 25:

1-151.

Sauer, W. H. H., M. J. Smale, and M. R. Lipinski. 1992. The

location of spawning grounds, spawning and schooling behaviour of the squid Loligo vulgaris reynaudii (Cephalopoda: Myopsida) off the Eastern Cape Coast, South Africa. Mar.

Biol. 114: 97-107.

Segawa, S. 1987. Life history of the

oval squid, Sepioteuthis lessoniana in Kominato

and adjacent waters central Honshu, Japan. J. Tokyo Fish. 74: 67-105.

_____, T. Izuka,

T. Tamashiro, and T. Okutani. 1993. A

note on mating and egg deposition by Sepioteuthis lessoniana in Ishigaki Island, Okinawa, Southwestern Japan. Venus (Jap.

J. Malac.) 52:101-108.

addresses: (corresponding author): (T.M.J.) Marine Biology, School of Biological

Sciences, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide, South Australia, 5001. Tel. +618 8201 5184. Fax + 61 8 8201 3015.

E-mail: <Troy.Jantzen@flinders.edu.au>. (1,N.H.) Deputy Head, School

of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, GPOBox2100, Adelaide, South

Australia, 5001. Tel. +618 8201 2007. Fax+ 61 8 8201 3015. E-mail: <Jon.Havenhand@flinders.edu.au>.

by Steve Reynolds

Since the

publication of my article “Numerous Nudibranch Findings” in our June 2005

Newsletter (No.322), SA diver Dennis Hutson continues to make more nudibranch

discoveries.

Since then Dennis has found nudibranchs such as Noumea haliclona, Thecacera

pennigera, Noumea closei, Discodoris concinna, Dendrodoris (?nigra)

and Hypselodoris saintvincentius. These discoveries are discussed later,

but let’s go back to some details about those nudibranchs discussed in the first article.

“Numerous

Nudibranch Findings” reported findings of Polycera

hedgpethi, Elysia Sp.

(E.?expansa), Flabellina Spp. (3)

and Aegires villosus by Dennis.

Each of

these species features in “1001 Nudibranchs” by Neville Coleman. Polycera hedgpethi, however,

is incorrectly spelled as Polycera hedgepethi in that book. (I, myself, spelled ‘opisthobranch’ incorrectly in my article.)

Our

Society purchased “1001 Nudibranchs” since my article was written. It is

primarily used for identification and classification work for our Photo Index

but it is available from our library for limited loan to Society members (mlssa

No.1050).

“1001

Nudibranchs” does not include SA in the distribution details given for Polycera hedgpethi, Elysia Sp. (E.?expansa)*,

Flabellina Spp. (3)

and Aegires villosus.

This means that Dennis’s information is quite important.

*It may

not have been made entirely clear in my article “Numerous Nudibranch Findings”,

but Elysia species

Elysia Sp. are

not nudibranchs at all. They are, in fact, sap sucking slugs (Order Sacoglossa).

“The Sea Slug Forum – Species List” gives the

following details for Elysia species: -

Order Sacoglossa, Superfamily Elysioidea, Family Elysiidae.

Elysia species

On 8th

June 2005 Dennis sent an email message to Nerida

Wilson (formerly of the SA Museum) to let her know that specimens of Polycera hedgpethi

had returned to the North Haven boat ramp. Nerida

is now working at the Department of Biological Sciences at Auburn University in

Alabama, USA. Dennis had been looking out for Polycera

hedgpethi every week and discovered

them again whilst collecting water for his aquarium. He told Nerida that the size of the animals was small, about 10mm.

“If you know their growth rate you should be able to work out when they

actually returned. They’re the first I’ve seen this year. The water temperature

has now dropped to 16 degrees C.”

Polycera hedgpethi

I later

asked Nerida if she had received Dennis Hutson's message about the late reappearance of Polycera hedgpethi.

She replied that she had and that she had managed to incorporate it into her

paper before it went to the printers.

“Just in

time!” she said. “It’s a very interesting observation. The name honours Joel Hedgpethi, a marine scientist that worked mostly in

California, I think...here you go, a quick web search found this...

“Joel

Walker Hedgpeth, 1911-, Californian pycnogonid taxonomist and ecologist, active between the

1930s-1980s [Hedgpethia turpaeva,

1973, Coboldus hedgpethi

(J.L. Barnard 1969), Laophontodes hedgpethi Lang, 1965, Chaetozone

hedgpethi Blake, 1996, Polycera

hedgpethi Marcus, 1964, Ammothea

hedgpethi, Elysia hedgpethi ].”

“The Sea

Slug Forum – Species List” gives the following details for Polycera

hedgpethi :-

Order Nudibranchia, Suborder Doridina,

Family Polyceridae, Subfamily Polycerinae.

On 12th

February 2005 Dennis found a tiny 5 mm long nudibranch in Gulf St Vincent on

Seacliff Beach. As usual, Dennis took a photo of the tiny critter and sent it

in to the Sea Slug Forum at http://www.seaslugforum.net

asking for it to be identified.

Polycera hedgpethi

Noumea haliclona

The Sea

Slug Forum is operated by Dr Bill Rudman, Curator of

Molluscs at the Australian Museum.

In his

response to Dennis, Dr Bill Rudman said: -

“Dear

Dennis,

This is

interesting on two counts. Firstly, I think it is a juvenile of Noumea haliclona.

This is interesting because, although it is known from New South Wales,

Victoria and Tasmania, this is the first record I know of it from South

Australia. As you will see from the Fact Sheet, its colour matches one of the

colour forms found in Tasmania. The second interesting point is that its rhinophores are fused. Instead of being a pair, there

is one large central rhinophore apparently in a

single large pocket. This is obviously a result of some fault during its

larval development. If you are interested, have a look at the fact sheet

where I have listed other developmental abnormalities”.

The fact

sheet included these details: - “This small chromodorid

is common in south eastern Australia both intertidally

and sublittorally from northern New South Wales, to

Victoria and Tasmania. It is one of the red-spotted colour group of chromodorids from this region and exhibits both colour

variation within a region [sympatric variation] & distinctive regional

colour forms [allopatric variation], which are

illustrated on this page. There are no distinguishing anatomical features

between the regional colour morphs. Externally, small scattered red or orange

spots, and a red or orange mark on the front of the rhinophore

club are the two characters which link these forms together. They feed on a

range of pink and yellow aplysillid sponges.

Best

wishes,

Bill Rudman”

According

to the fact sheet, Noumea haliclona (Order Nudibranchia)

is of the Suborder Doridina, Superfamily Eudoridoidea

and Family Chromodorididae.

The fact

sheet can be seen at: -

http://www.seaslugforum.net/factsheet.cfm?base=noumhali1

. Noumea haliclona

features on page 83 of “1001 Nudibranchs”.

On 18th

June 2005 Dennis was diving solo at Outer Harbor when he discovered another

tiny (12mm) nudibranch on some Caulerpa (racemosa?). Dennis took this

photograph of the colourful little nudibranch and later sent it to me for

identification.

Noumea haliclona

Thecacera pennigera

I was

able to identify it from Neville Coleman’s book “Nudibranchs of the South

Pacific” as being Thecacera pennigera. I still suggested to Dennis that he send his

photo in to the Sea Slug Forum. He did that on the 20th June, with

the following message: -

“Can you

please confirm this is Thecacera pennigera?

Locality:

Outer Harbor, Adelaide, South Australia. Depth: 3 metres. Length: 12 mm. 18

June 2005. silty. Photographer:

Dennis Hutson.

Is it

native to Adelaide, South Australia?

Cheers,

Dennis Hutson”

Dennis

soon received the following reply from Dr Bill Rudman:

-

“Dear

Dennis,

Yes this

is Thecacera pennigera.

Your question about where it comes from is quite interesting. It was originally

described from England so we have assumed that it is a North Atlantic species.

However it has since been found in many parts of the world as you will see from

the Fact Sheet and accompanying messages. It feeds on bryozoans which are part

of the 'fouling community', a name for plants and animals which grow on

hard surfaces, and in particular, the bottom of boats. We have assumed

that this species has spread from the North Atlantic on the bottom of boats.

However most species of Thecacera are found in

the Indo-West Pacific region, and as you will see from

looking at the photos on the Forum, there is much more colour variation in

animals from the Pacific than from the North Atlantic. This could suggest that

the Pacific is the original home of this species and what we now find in the

North Atlantic is a population based on a few Pacific animals with small spots

that were transported there on the bottom of sailing ships two centuries ago.

I guess

this could be tested by DNA analysis.

Best

wishes,

Bill Rudman”

(These

details can be found at http://www.seaslugforum.net/display.cfm?id=14077

.)

The fact

sheet accompanying Bill’s reply indicated that Thecacera

pennigera (Order Nudibranchia)

belongs to the Suborder Doridina, Family Polyceridae and Subfamily Polycerinae*.

It said that the species had been originally reported from the Atlantic coast

of Europe, but it is now known from South Africa, West Africa, Pakistan, Japan,

Brazil, eastern Australia and New Zealand.

The fact

sheet can be seen at :-

http://www.seaslugforum.net/factsheet.cfm?base=thecpen

.

*This

makes Thecacera pennigera

a close relative of Polycera hedgpethi which shares the same details.

“1001

Nudibranchs” features both Thecacera pennigera and Noumea haliclona, but the book does not include SA in the

distribution details given for either. Once more, this means that Dennis’s

information is quite important.

Thecacera pennigera is featured on page 47 of “1001 Nudibranchs” and page 14

of “Nudibranchs of the South Pacific”.

Thecacera pennigera

Again, as

with Polycera hedgpethi,

CRIMP’s “A Guide to the Introduced Marine Species in

Australian Waters” by Dianne M Furlani has a page of

details about Thecacera pennigera

under “Mollusca” (updated May 1996). (CRIMP is

the acronym for Centre for Research on Introduced Marine Pests.) Also as with Polycera hedgpethi,

this page also features a Richard Willan and Neville

Coleman 1984 photo of the nudibranch. This appears to be one of the same photos

(AMPI 73) featured in “1001 Nudibranchs” and the same one featured in

“Nudibranchs of the South Pacific Vol.1” by Neville Coleman.

(AMPI is

the Australasian Marine Photographic Index which is curated

by Neville Coleman. According to Neville, the Index is “a comprehensive

scientifically curated visual identification system

containing over 150,000 individual transparencies covering almost every aspect

of aquatic natural history”. The colour transparencies of living animals and

plants in the Index are “cross-referenced against identified specimens housed

in museums and scientific institutions”.)

“A Guide

to the Introduced Marine Species in Australian Waters” says that, although Thecacera pennigera is

a Polycerid, it “differs consistently from Polycera in (both) absence of velar process and presence of

rhinophore sheath”. Also, “body

tapers to long foot, 2 lateral extensions posteriorly, and no velar process”.

According

to the glossary in both “1001 Nudibranchs” and “Nudibranchs of the South

Pacific Vol.1”, a ‘rhinophore (rhinophoral)

sheath’ is an “upstanding flange from the antero-lateral

part of the mantle (of dendronotacean nudibranchs)

into which the rhinophore can be contracted”. The

glossary says that a ‘rhinophore’ is “sensory

tentacle on the head or anterior section of the mantle of opisthobranchs”.

I also

wanted to know what ‘velar’ was. I couldn’t find the word in any of the

glossaries that I checked out. It was, however, shown in a diagram of a dorid nudibranch in “1001 Nudibranchs”. There also seemed

to be a connection between ‘velar’ and ‘velum’. It so happened that I had the

opportunity to ask Greg Rouse at the SA Museum about this matter.

“Do you

know much about nudibranchs?” I asked him. “Can you explain what velar/velum

are?”. Greg suggested that his partner, in the USA

(who happens to be Nerida Wilson) would be the best

person to help me. He said that he had passed my query on to her.

Nerida soon replied to my query, saying that “The velum is the

part of a nudibranch larva that is covered with cilia that help it swim/feed.

It has two (velar) lobes. There is a nice picture of a larvae where you can

clearly see the foot, and the velar lobes poking out from the shell on the sea

slug forum at :-

http://www.seaslugforum.net/factsheet.cfm?base=larvshel

.

I think

during metamorphosis that the velar lobes are reabsorbed into what becomes the

mantle. Hope it helps. Nerida”

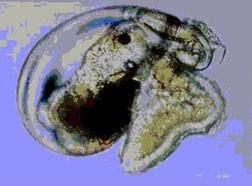

I checked

out http://www.seaslugforum.net/factsheet.cfm?base=larvshel

where I found the following picture by Yoshi Hirano: -

Yoshi Hirano's picture clearly

showing the transparent larval

shell of the aeolid nudibranch

Facelina bilineata.

This

would seem to be the picture referred to by Nerida

“of a larvae where you can clearly see the foot, and

the velar lobes poking out from the shell”.

Incidentally,

Neville Coleman gives most nudibranch species a common name. For example, he

calls Thecacera pennigera

“Winged Thecacera.” Noumea haliclona is called “Sponge Noumea”

and Aegires villosus

is called “Shaggy Aegires.” Polycera

hedgpethi is called “Hedgepeth’s

Polycera” (should be “Hedgpeth’s

Polycera”). The opisthobranch

Elysia expansa

is called “Wide Elysia.”

Dennis is

keeping his specimen of Elysia Sp. (E.?expansa) in his home

aquarium. The opisthobranch is doing very well in the

tank and it has laid eggs on a couple of occasions.

On 13th

August 2005 Dennis photographed a small specimen of the Sweet Ceratosoma,

Ceratosoma amoena at the Glenelg Tyre Reef.

Ceratosoma amoena

Ceratosoma amoena is featured on pages 64-5 of “1001 Nudibranchs” and page

39 of “Nudibranchs of the South Pacific”. According to “1001 Nudibranchs”, Ceratosoma

amoena (Order Nudibranchia)

belongs to the Family Chromdorididae.

There has

been some confusion over the correct scientific name for the Sweet Ceratosoma.

I have come across the name Ceratosoma amoenum

in place of Ceratosoma amoena. Nerida Wilson says that Ceratosoma amoena

is the correct name. She explains, however, that the species used to be placed

in the genus Chromodoris (as Chromodoris amoenum).

It was later moved into the genus Ceratosoma and the species name was then

changed to match the gender of the new genus (Ceratosoma amoena).

Later on,

Nerida explained the above details to me once more by

saying, “The animal was first called (Chromodoris) amoenum,

but when it was put in to the genus Ceratosoma instead, the specific name was

changed to amoena to be in agreement with the

gender of the genus name Ceratosoma”.

It seems

then that different genus are considered as different

gender. Nerida told me “It’s confusing to know which

genus name is feminine or masculine, etc, and when a change is needed. However,

while it is strictly correct to change the species name to match (the gender of

the genus name), not all people stick to this. But for your species, amoena is the correct and common usage nowadays” she

said.

On 10th

July 2005 Dennis sent me two more photos of nudibranchs that he had found on

the Glenelg Barge the day before. He also sent both of the photos on to Nerida Wilson, Thierry Laperousaz,

Senior Collection Manager for Marine Invertebrates at the SA Museum’s Science

Centre and the Sea Slug Forum. Dennis and I had several discussions about the

identification of the two nudibranchs but Nerida was

the first person to respond with an ID.

“I think

it is Noumea sulphurea”

she said, “although there is a possibility it is N.closei.

You may be able to see better whether there are any

small orange specks on the back, which will likely indicate N.closei”.

Dennis

also thought that it might be Noumea sulphurea. He directed me to http://www.seaslugforum.net/factsheet.cfm?base=noumsulp2

.

The web

page features two photos of Noumea sulphurea. They were both said to be the “Bass Strait

colour form” (both from Tasmania in 1985). The distribution for Noumea sulphurea was

given as being “Southern Australia - Tasmania, Victoria & South

Australia”.

The web

page went on to say that “Specimens from Tasmania, Victoria and South Australia

differ from New South Wales animals in having regularly spaced white specks all

over the dorsum except for a clear band near the edge, the specks apparently

being formed from aggregations of subepithelial

granules. In some specimens there is also an aggregation of these granules

right at the edge of the mantle to form a broken white line along the edge. The

colour of the orange spots is also much less brilliantly opaque than New South

Wales animals, the spots often being almost invisble

in smaller specimens.

This

‘Bass Strait colour form’ is very similar in colour to Noumea

closei and the yellow Tasmanian colour form of Noumea haliclona”.

Dennis’s

enquiry was posted to the Sea Slug Forum site on 20th July 2005 at http://www.seaslugforum.net/display.cfm?id=14265.

Bill Rudman said that it was, in fact, Noumea closei. The

web page read: -

“Noumea closei from

South Australia (From: Dennis Hutson)”

Ceratosoma amoena

Noumea species

Could

this please be identified and is it native to South Australian waters?

Locality:

wreck of the Barge, Glenelg, South Australia. Depth: 16 m.

Length: 10 mm. 9 July 2005, Deck of the wreck, Photographer: Dennis Hutson”.

Bill Rudman responded with: -

“Dear

Dennis,

This is Noumea closei, which

is known from Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia. Have a look at the Fact

Sheet for more information on it and the other similarly coloured species.

Best

wishes,

Bill Rudman”

The facts

sheets for Noumea closei

and Noumea sulphurea

are http://www.seaslugforum.net/noumclos.htm

and

http://www.seaslugforum.net/noumhali1.htm

respectively.

Dennis

told me that he thought that it was N.sulphurea

because of this other link - http://www.seaslugforum.net/display.cfm?id=6309

. “Bill mentions the white marks on top” said Dennis. The web page read: -

“Noumea closei from

South Australia

March 10,

2002

From:

Stuart Hutchison

Hi Bill,

Here’s

one were not sure about from the wreck of The South Australian,

Adelaide, South Australia on 26 Sep 1999. Depth 20m, length

15mm.

Regards,

Stuart.

Thanks

Stuart,

I am

pretty sure, from the white marks, that this is Noumea

closei. However if you look at the Bass Strait

colour form of Noumea sulphurea

you will see it is almost identical externally. There is an interesting story

attached to how I first realised there were two species involved. N. closei when preserved in formalin turns dark brown,

sometimes almost black, while Noumea sulphurea gradually loses all its colour, becoming

translucent white. One day, when I was choosing some specimens to dissect, I

decided I had better check some dark and some light coloured ones just in case

I had missed something. To my great surprise I found their radular

morphology was quite different.

Using the

preserved colour of a slug is not the most practical way to identify a species,

but as with species of Rostanga, sometimes

external shape and colour just isn't enough.

Best wishes,

Bill Rudman”

Noumea sulphurea is featured on page 84 of “1001 Nudibranchs” and page 42

of “Nudibranchs of the South Pacific”. Neville calls it a Sulphur Noumea. Noumea closei is not in either book.

We still

don’t know, at the time of writing, what species Dennis’s second photograph is.

Neither Nerida Wilson, Bill Rudman or Neville Coleman have been able to identify

it.

Noumea species

An aeolid nudibranch on the Barge at Glenelg

After

viewing MLSSA’s copy of “1001 Nudibranchs”, Dennis ordered a copy for himself to assist with identifications. He found that one of

Nerida Wilson’s nudibranch photos is featured on page

89. It is a Doriopsis

pectin (Blue Doriopsis).

Dennis

photographed specimens of Discodoris concinna and a Dendrodoris

whilst diving at Outer Harbor. He reported the discoveries to Thierry Laperousaz at the SA Museum.

Thierry

advised Dennis that he thought that Discodoris

concinna was rare in SA. Dennis has since

collected a specimen for the museum.

An aeolid nudibranch on the Barge at Glenelg

Discodoris concinna

Discodoris concinna is featured on page 23 of “Nudibranchs of the South

Pacific”. Thierry thought that the Dendrodoris that

Dennis had photographed was Dendrodoris nigra. Dennis feels that it is actually Dendrodoris fumata

as it is more commonly found in our waters. He says that there is a subtle

difference in the gill structure but they are very difficult to tell apart.

Discodoris concinna

Dendrodoris (?nigra)

Stuart

Hutchinson thought that he had taken some photos of Dendrodoris

nigra at Edithburgh jetty in January 1999. He

sent two photos to the Sea Slug Forum in February 2000. Bill Rudman responded as follows: -

“Dear

Stuart,

This is Dendrodoris fumata,

not Dendrodoris nigra.

Have a look at my comments on each page to see the differences ( http://www.sealugforum.net/dendfuma.htm

and http://www.seaslugforum.net/dendnigr.htm

).

These two

species have been confusing us for over a century as both have the same range

of colour forms. One good difference seems to be the shape and number of gills.

In D. fumata there are a few (usually 5) large

gills, which are usually extended out to the mantle edge. In D. nigra there are many small gills arranged in a

cup-shaped circle. In both your photos I think I can see parts of the bright

yellow egg ribbon. It also appears that the sponge they are on is a food

source.

Best

wishes,

Bill Rudman”

These

details, with the two photos, are available at :-

http://www.seaslugforum.net/display.cfm?id=1818

.

Dendrodoris fumata is featured on page 86 of “1001 Nudibranchs” and Dendrodoris nigra is

featured on page 87. Neville Coleman calls Dendrodoris

fumata Hazy Dendrodoris and

Dendrodoris nigra

Black Dendrodoris. “1001 Nudibranchs” says that

both belong to the Dendrodorididae family.

Dennis

photographed a Hypselodoris species of nudibranch

whilst diving at the Blocks at Glenelg on 21st November 2004. Someone suggested

that it was Hypselodoris infucata but Dennis thought that it might be Hypselodoris saintvincentius

as this species is more commonly found in our waters. As he understands it,

the difference is in the colouring. On 26th

August 2005 Dennis posted the following details on to the Sea Slug Forum: -

“Could you please confirm the id of this critter? The photo was taken at a site

known as the Glenelg Blocks, which is located approx. 500m off the beach of

Glenelg, South Australia, Gulf St. Vincent. I was told it was Hypselodoris infucata

but I thought it might be Hypselodoris saintvincentius. I understand there is a slight

difference in colour. Thanks for your help.

.jpg)

Dendrodoris (?nigra)

Hypselodoris saintvincentius

Locality:

Glenelg Blocks off Glenelg Beach, South Australia, Southern Ocean. Depth: 5 m.

Length: 40 mm. 21 November 2004. Rocky bottom Photographer: Dennis Hutson”

Bill’s

reply was as follows: -

“Dear

Dennis,

Your

animal is Hypselodoris saintvincentius.

As I discuss in a recent message [http://www.seaslugforum.net/find.cfm?id=14285],

it is not that easy to separate from H. infucata.

Best

wishes,

Bill Rudman”

Hypselodoris infucata is featured on page 80 of “1001 Nudibranchs”. Neville

Coleman calls it Painted Hypselodoris. “1001

Nudibranchs” says that, like Noumea closei, Noumea sulphurea and Ceratosoma amoena,

Hypselodoris infucata

belongs to the Chromodorididae family.

In August

2005 Nerida asked Dennis and I to arrange for the

collection of Polycera hedgpethi

sspecimens for her. She said that she was trying

to set up a project that uses the DNA sequences of all P.hedgpethi

populations worldwide, to try and determine which populations are connected by

gene flow, etc.. “I am hoping to be able to determine where the natural range

of Polycera was in the world, and if it is truly

introduced or not. This requires many more specimens than Dennis collected for

me last year. Is there any chance that you might be able to help, or know

someone who may? I basically need about 25 specimens,

and someone to take them into the museum where Greg or Thierry can fix them for

me” she said.

That same

month (August 2005) Dennis and I dived at Outer Harbor in low visibility. We

couldn’t find any Polycera hedgpethi but Dennis managed to find another Elysia species. He also photographed and collected

another unusual nudibranch.

Hypselodoris saintvincentius

An unusual nudibranch

found at Outer Harbor

After the

dive Dennis studied the photograph and “1001 Nudibranchs”. He suggested in an

email message to me that it may possibly be a Discodoris

lilacina (p.56) or Dendrodoris

albobrunnea (p.86). Whilst “leaning towards the

first” he decided to post it onto the Sea Slug Forum for confirmation.

On Sunday

28th August I snorkeled at Dock 1 in the Port River to search for

specimens of Polycera hedgpethi

for Nerida. I didn’t have any luck at all and advised

Nerida and Dennis. Dennis reported that he had

collected 4 specimens for her from the North Haven boat ramp. This gave Dennis

the opportunity to take some more photos of the species. He said that he was

taking them in to the SA Museum alive for Thierry to fix for Nerida.

An unusual nudibranch found at Outer Harbor

Dennis

has set up his own web site which features different galleries of his photos,

both above and below water. The address for the site is :-

http://members.ozemail.com.au/~dghutson/

.

Many of

Dennis’s nudibranch photos are being posted to the site.

Many

thanks to Dennis Hutson, Nerida Wilson, Thierry Laperouzas and Bill Rudman for

their considerable assistance with the above details.

REFERENCES:

“Nudibranchs of

the South Pacific Vol.1” by Neville Coleman, Sea Australia Resource Centre,

1989, ISBN 0 947 325 02 6.

“1001

Nudibranchs” by Neville Coleman, Underwater Geographic P/L, 2001, ISBN

0947325255 – mlssa No.1050.

“Numerous

Nudibranch Findings” by Steve Reynolds, MLSSA Newsletter June 2005 (No.322).

Australasian Nudibranch News 2:4

(Volume 2 (4): 3, December 1999)

The Sea Slug Forum – Species List

PHOTO CREDITS

1. Dennis Hutson of Elysia species

2. Dennis Hutson of Polycera hedgpethi

3. Dennis Hutson of Noumea

haliclona

4. Dennis Hutson of Thecacera pennigera

5. Yoshi Hirano

of the transparent larval shell of the aeolid

nudibranch Facelina bilineata.

6. Dennis Hutson of Ceratosoma amoena

7. Dennis Hutson of Noumea closei

8. Dennis Hutson of an aeolid nudibranch found on the Barge at Glenelg

9. Dennis Hutson of Discodoris concinna

10. Dennis Hutson of the Dendrodoris (?nigra)

11. Dennis Hutson of Hypselodoris

saintvincentius

12. Dennis Hutson of an unusual nudibranch found at Outer

Harbor

Recent Requests to Our Society for Information

by Steve

Reynolds

Our Society occasionally receives

requests (usually by email) for information on marine topics. A few such

requests, and subsequent replies, have been put together below: -

Late in 2003 we received the

following request for information:-

“Hi… I’m a

Bachelor of Science student (Biology major) looking for some information on the

Leafy Seadragon for an ecology assignment. It’s only for my 2nd year

Ecology essay, but it’ll be invaluable. As my studies continue, I plan to focus

on the marine ecology of the Hallett Cove/Marino area where I live – a very

interesting and unique little bit of coastline. I’m actually a plant science

fanatic, so my special interest is actually the local seaweed!

Cheers,

Anissa Lato”

I was able to

provide Anissa with the references that she requested

for her assignment. I asked her to keep in touch and let us know how she gets

on with it.

The following message then came from

Heather Wadley in January 2005.

“Subject: I am in

search of information on the Leafy Sea Dragon.

Dear MLSSA

members,

My name is

Heather Wadley, I am a 12th grade student at a

Massachusetts school in the United States. I am taking an oceanography class,

and my teacher, Mrs. Streck is having us do a project

on a oceanic creature. I have looked online for the

internal and external structure of the Leafy Sea Dragon. I stumbled across your

newsletter when doing a search online, and saw that you offered the information

about the anatomy of a Leafy Sea Dragon, and I was wondering if it might be

possible for you to share the information, if you have pictures that are

possibly labeled, or not labeled. I greatly appreciate your help if you can

help me or not with the pictures. Again, thank you very much for your

assistance.

Sincerely,

Heather Wadley”

We sent the following reply to

Heather: -

“Hi Heather

Firstly, I have

attached two pictures from our Photo Index. You will find lots of articles

about the Leafy in our September 2004 newsletter on our web site. You will find

some more photos there. I have also attached a seadragon reference list that I

have compiled.

Here are some

details about Dragon Search’s Code of Conduct.

‘DIVING WITH

DRAGONS - CODE OF CONDUCT’

The ‘Diving with

Dragons - Code of Conduct’ sets out a few simple guidelines that divers can

follow to reduce their impact on seadragons. The “Diving with Dragons - Code of

Conduct” asks divers to: -

Leave seadragons

where they are;

Look but don't touch;

Respect their home range and avoid herding;

Avoid moving seadragons up or down in the water column;

Accept sea lice on seadragons in moderation;

Watch your feet and fins;

Take special care with male seadragons carrying eggs;

Turn the lights down when observing at night;

Clean up discarded fishing line found;

Dive right and watch your gear;

Respect the marine environment;

Remember fisheries regulations; and

Respect marine reserves.”

Hope that this

all helps.

Regards,

Steve Reynolds”

The following request came from

Robin Sharp in April 2005.

“Subject: Marine

Plan rare species Upper Spencer Gulf

Hi,

Appreciate if

you could email me back some information on the following species. Apparently

they are a relic species of interest within the Upper Spencer Gulf Marine plan.

I would like to obtain a photograph of these in order to better understand what

they actually are. Can you help?

1) A

flatworm (ancoratheca sp.)

(2) A

nudibranch (Discodoris sp.)

(3) An ophiuroid (Amphiura sp.)

Best Regards,

Robin Sharp,

Port Augusta”

We sent the following reply to

Robyn: -

“Hi Robyn

1) Flatworms

are Polyclads (Order Polycladida).

They belong to the Phylum Platyhelminthes. There is a

chapter (Chapter 5) about them in the book ”Marine

Invertebrates of Southern Australia – Part 1” edited by SA Shepherd & IM

Thomas. Ancoratheca australensis

is the first species described in the chapter. It is said to be recorded from

upper Spencer Gulf. The brief description says that the body is “oval, of firm

consistency, to about 10mm long. Dorsal surface light brown, dappled with dark

spots, except anteriorly and marginally where body is

whitish. Very small marginal eyes; minute eyes spread fanwise over cepahalic region to merge with marginal eyes”. A few

specimens of flatworms are pictured in the book – plates 22.4, 22.5, 22.6 23.1.

One book that specializes in Polyclads is “Marine

Flatworms, the World of Polyclads” (author unknown)

which is available for $39.95 (+ postage) from books@motpub.com.au .

2) Nudibranchs

are an Order of ophistobranchs (sea slugs) – Order Nudibranchia. Dorid nudibranchs

are a Family of nudibranchs – Family Dorididae. Discodorids are included in the Dorid

family. Three species of discodoris are pictured in

Neville Coleman’s book “”Nudibranchs of the South Pacific” (pages 22 –3). This

book is also available from books@motpub.com.au

at the price of $16.50.

3) Ophiuroids are brittlestars, a

class of starfish. Brittlestars belong to the Class Ophiuroidea.

The book ”Marine Invertebrates of Southern Australia-

part 1” edited by SA Shepherd & IM Thomas lists several species of Amphiura brittlestars (belonging

to the Family Amphiuridae) on page 437. Only two of

these species are described in the book – Amphiura constricta & Ophiocentrus pilosus (on page 425). Amphiura

are said to have “two squarish papillae at apex of

each jaw”. Amphiura constricta

is said to have “one erect distal oral papillae on each side of each jaw,

separated from the tooth papilla by a wide gap (Fig 10.15e on page 427). It is

said to be “A widespread and common species growing to 7mm disc diameter, with

arms up to 45mm long. The disc is fully scaled above and below, and the arms

bear 6-8 short spines on each segment. The tentacle pores are covered by a

single, large oval scale, and there is one distal oral papilla on each side of

the jaws. The radial shields are longer than wide, separated and divergent. The

disc is grey and the arms are banded light and dark. The species lives in algal

turf and amongst bryozoan and sponge rubble”.

Ophiocentrus pilosus is said to have “one or two squarish

apical oral papilla and one or two distal papillae” and “Disc scales bearing

simple short spinelets, no tentacle scales”

(Fig.10.15c on page 427). It is said to be “A large simple-armed brittlestar gowing to 18mm across

the disc with arms 140mm long. It is characterised by

having a Amphiura-type mouth

structure, with tall distal oral papilla on each side of the jaws, but it is

also completely lacks tentacle scales, and its disc is covered with small

scales and numerous short spinelets. It has up to 10

somewhat flat-tipped arm spines on each segment, and the lowermost are the

longest. A soft sediment dweller, this species is known mostly from SA to NSW”.

Our Photo Index

of SA Marine Life features a few photos of flatworms, dorid

nudibranchs and brittlestars. These photos can be

viewed on our web site at www.mlssa.asn.au

- flatworms on pages 16 & 17, dorid nudibranchs

on pages 1-3 and brittlestars on pages 8 & 9.

Much of the above

details are very involved but we trust that it helps a little.

Cheers

Steve Reynolds”

This request came from Des Fuller in

March 2005: -

“Hi.

I have been

trying to find out some info on the life cycle and growing time for Razor fish.

We collect them (to eat) each year on our holidays on Gulf St Vincent in

SA. But there are a lot of small ones and we wonder how fast they grow, etc...

Any info would be gladly received.

Yours in nature,

Des Fuller,

Port

Pirie.”

We sent the following reply to Des:

-

“Hi Des,

It has been

suggested that razorfish are now threatened or endangered. Sorry that we cannot

help you re life cycle, etc.. Suggest that you contact

SARDI at sardi@saugov.sa.gov.au .

Cheers,

Steve”

Des soon

replied as follows: -

“Hi Steve,

Thanks for your

referral to SARDI. Suzanne was very helpful and has sent me some papers on the

findings of surveys done in Gulf St Vincent, and it

has answered all our questions.

Thanks again.

Regards,

Des”

That last enquiry had been the

second recent one regarding razorfish. In September 2004 Adam Browne had sent

us an email request. These details were published in our March 2005 Newsletter

(No.319): -

“Hi,

I hope you don’t

mind general enquiries; I'm looking for information on razorfish, which I'm

told are a kind of shellfish that lives in South Australian waters. I was

wondering if there's anything you could tell me about their distribution around

the Australian coast, especially here in Victoria, and whether they are an

endangered species or are allowed to be fished.

Thank you,

Adam Browne”

We sent the following email reply to

Adam: -

“Dear Adam

You are correct

about razorfish being a kind of shellfish that lives in South Australian

waters. It seems that they occur across southern Australia from WA to NSW,

usually in seagrass beds or sand flats in bays and estuaries. They are not

considered to be an endangered species and they are allowed to be fished in SA.

There are, however, bag limits for the species Pinna bicolor

in SA waters. The department responsible for SA’s fishing regulations, Primary Industries and Resources SA (PIRSA),

currently applies a bag limit of 50 for this species and a boat limit of 150.

Check with your own State’s authorities for fishing regulations in Victoria.

Below are some more details about razorfish: -

Razorfish are

marine bivalve molluscs from the family Pinnidae.

They are also known as Pinna, Razor-shells, Pen Shells and Fan Shells. A simple

description of razorfish can be found in “Seashells of the World” (A Golden

Guide). This little book says that they are “large and fragile, live in soft

sand anchored by a silky byssus”. A byssus is a tuft of dark brown threads*.

A more

complicated description about them is found in “Molluscs” by JE Morton. This

book says that “They have long and wedge-shaped equal valves, and are unique in

being embedded upright in the sand and secured there by a byssus.

Each byssus thread is attached to a sand particle,

and the whole structure gives great stability in a soft substrate. The fan

shell is immobile and the foot and anterior end are greatly reduced. The

posterior or uppermost part of the shell is broad and triangular, composed of

horny conchiolin, only thinly calcified. There is a

wide mantle gape at the broad end, with thickened lips, and,

. . . there are efficient ciliary and mucous

tracts for cleansing the mantle cavity of sediment. The greater part of the

mantle in Pinna is free of attachment to the shell, and its edges can be deeply

withdrawn and protected from injury by special pallial

retractor muscles”.

The book

“Australian Seashores” by Isobel Bennett says that the Pinna are

known as razor-shell because of their sharp (ventral) edges. When these sharp

edges are all that protrudes from sand they can cause serious injury to bare

feet.

*The original

version of “Australian Seashores” by WJ Dakin gives

more information about razorfish and quite some details about the byssus. It refers to the byssus

as “a curious bunch of anchoring threads”. It goes on to say that “The

production of this byssus is a function of the foot

found only in bivalve molluscs. The byssal threads

are secreted by a gland in the foot, which thus becomes an organ for

attachment”.

We hope that this

information helps.

Yours sincerely,

Steve Reynolds

Secretary

Marine Life

Society of SA”

Other request details that have been

published in our Newsletter include the following one received in October 2003

about a Catfish sighting at the Port Noarlunga Reef. The enquiry was sent on to

us by James Brook. It was published in our March 2004 Newsletter (No.308): -

“Hi James

I'm not sure if

this is of interest to you or Reefwatch, but I'll let you know in case it is. On a night dive at Noarlunga Reef last night we saw an unusual fish

(we thought was unusual anyway). At first we I thought it was a rock

ling but it had more than two barbels (and I think

more than four as well). I believe from my fishing book that it was an Estuary

Catfish (Cnidoglanis macrocephalus)

as the body was more rock ling shaped than the more stout bodied eel-tailed

catfish (which is freshwater anyway). I just thought

that this was an unusual sighting as Noarlunga reef is neither

an estuary or brackish water which I believe they are found in. Also,

according to the species location in my book, they are found in Queensland /

Victoria and Western Australia. They're probably very common here but I haven't

seen one before. Also it was about 1-1.2m, so quite big as well. We found it

about 100-200m north of the jetty. If you can give me any feedback on whether

this is an estuary catfish, and how common they are around here, I would

appreciate it. Is there a database that this type of thing goes onto, on the

website, or do I just email you the info? Hope this is of some use.

Cheers

Nick”

James wanted a response from me and

so I sent him the following email reply: -

“Hi James

I keep my own

database of fish sightings at Port Noarlunga reef. I have recorded Estuary

Catfish for the area. These are a marine species and they can be quite large.

They occur in estuarine and coastal waters. They should have 8 barbels on their head. Max size is said to be just 91cm. Everything underwater looks 1/3 bigger i.e. 1.2m.

Steve”

Philip Hall reminded me of various

articles published in our Newsletters and Journals so a later email (to Nick?)

read: -

“Hi Nick,

Further to my

last email re your catfish sighting, David Muirhead has written an article

about a catfish sighting at Port Noarlunga. See the article “A Footbridge Too Fra” in either our December 2000 MLSSA Journal or our March