Marine Life Society of

South Australia Inc.

Newsletter

November 2005 No. 327

“understanding,

enjoying & caring for our oceans”

Next Meeting

This will be the November Meeting and will be held at the Conservation

Centre, 120 Wakefield Street, Adelaide on Wednesday 16th November

commencing at 7.30pm.

Our speaker will be John Emmett who will be discussing MPA’s.

Contents

Queenscliff Marine Discovery Centre (Philip Hall)

Greg Rouse’s Marine Worm

(& Feather Star) Research Part 1 (Steve Reynolds)

This is the final newsletter for 2005 and I would

like to take this opportunity to wish everyone a very Happy Christmas and a

really great New Year. I look forward to seeing you all at the first meeting in

2006 on the 18th January.

There will of course be a Journal sent out to

members in December. At the time of writing this I am not certain if a PDF

version will be possible due to the large graphic content which means the size

might be too great to send. It will be on our website in colour of course.

Philip Hall

REMINDER

Articles for YOUR Newsletter are always

required. The more people who write articles then the wider the topic spread.

Please do not leave it up to just a few. Articles of any length are welcome.

This Newsletter

The hardcopy of the Newsletter is in black and white as usual. If members prefer a colour PDF version then please email me.

Queenscliff Marine

Discovery Centre

by Philip Hall

During our short

September holiday in Melbourne to see the Dutch Masters display at the Art

Gallery we went via Queenscliff so we could visit the Marine Discovery Centre

there.

It used to be

housed in a building near the Sorrento ferry terminal. It was rather run down

when we visited it some years ago so when we heard it had been recently rebuilt

we decided to pay it a visit. It is now housed in an award winning building a

couple of kilometres before the town itself.

As you can see

from the picture much care has been taken with the design from environmental

and aesthetic points of view.

The Centre opens

at 10.00am so we were the first there. The friendly staff member warned us that

a large group of very young children was expected so we quickly entered the

main area. We stared in amazement at the large number of aquaria in view, of

different sizes and beautifully clean and well lit built into the walls.

The tanks were

all full of creatures and were often dedicated to just one species. For example

the seajellies had their own tank as did the octopus

and the seahorses. Others had to share and many familiar creatures and fish can

be studied.

One tank

contained the Pacific Seastar; I have never seen such a large seastar before.

They were huge.

The only

criticism we had was the large touch pool in the centre of the floor. (You must

know my views on the handling of marine creatures). In it were mainly seastars

and urchins. Again the water was crystal clear and beautifully lit. Small

platforms around the outside were arranged for smaller children to stand on.

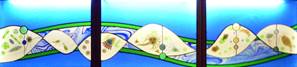

A separate

teaching room was equipped with TV and video, comfortable seats and carpet and

plenty of items to inspect around the walls. One wall had a beautiful glass

mural built into it. (Below)

Other areas

included one with so many items we could have spent hours there checking them

all out. The way they were displayed was excellent. They were in small wooden

boxes, some were open and others with more delicate items had plastic fronts.

One wall faced

out onto Port Philip Bay and long slit windows low down would enable children

(or crouching adults) to watch the many birds on the water or in the reed beds.

The Centre is

only a small part of the complex. Other organisations occupy the rest and I

assume they are all marine based.

We left in time

to catch the 11.00am ferry to Sorrento very impressed with the quality of the

Centre and vowing to return in a few years time to see how it progresses.

All in all well worth a visit the next time you

are in the area. By the way, it is only open on weekdays.

Greg Rouse’s Marine Worm (& Feather Star)

Research

by Steve Reynolds

I first heard

about the work of Dr Greg Rouse from the SA Museum when I read The Advertiser

dated 22nd March 2002. There was a report about a student from the

University of Adelaide studying feather stars. The student was Lauren Johnston and

her study was said to be “being overseen by museum research scientist and

marine expert Greg Rouse”. (More on this later.)

On 6th

May 2002 The Advertiser reported that Greg had an ongoing mystery about a

strange, glowing blue worm living in the mud at St Kilda in SA. Anglers had

long told stories about the strange, mysterious worm which could grow as long

as 1m.

Greg had not

long arrived in SA when he found a jar of the strange worms in the SA Museum

archives, together with a manuscript-length analysis on the worm. This had been

written by the late Dr Shane Parker, a former museum researcher. He wrote it

about 1992, just before he died. The jar of specimens had been lost during a

‘reshuffle’ at the museum. Once rediscovered by Greg, it became one of his

major projects. The blue-glowing worm was a eunicid,

a species of worm from the family Eunicidae. Greg

plans to name it in honour of Dr Parker.

In that May

issue of The Advertiser, Greg was calling for anyone finding unusual sea

creatures to let him know about it immediately. The article also reported that

Greg had co-authored a book about polychaete worms

with Fredrik Pleijel, the French scientist, in 2001.

That book would be “Polychaetes” by GW Rouse & F Pleijel, Oxford University Press, London, 2001. Greg has

still to find a live specimen of the blue worm.

Polychaetes are bristle worms which form part of the Phylum Annelida that also includes leeches and earthworms.

Greg was in the

news again in October 2003. The Advertiser dated 4th October

reported more about Greg’s work including how he would take pictures of marine

creatures through a stereo-microscope. The pictures were usually breathtaking

and he entered one of them in the Nikon 2003 Small World Photomicrography

Competition.

His photo was of

a polychaete worm, Myrianida

pachycera (formerly Autolytus

pachycerus) (Family Syllidae),

collected from Bondi in New South Wales. It can be

seen on the first (title) page of the web page at

http://tolweb.org/tree?group=Annelida&contgroup=Bilateria

.

It is the first

of four species featured there.

(Syllids (species from the Family Syllidae)

are described in “Marine Invertebrates of Southern Australia – Part 1” (Marine

Inverts. 1) as being from “a diverse group of worms”. They are described in

detail on pages 241-2 of the book edited by SA Shepherd and IM Thomas.)

The special

microscope magnified the worm 60 times. The shot won him Second Prize out of

about1200 entries in the photo competition.

Autolytus pachycerus

Greg said that Myrianida pachycera

is fairly common and can be found on algae on inter-tidal rocks all around the

SA coast. “The worm is about a quarter of the length of a fingernail, people

are usually walking on these things,” he said.

It was reported

by The Advertiser at the time that the gallery of images entered in the photo

competition could be seen at www.nikon-smallworld.com

.

In 2004 the

Marine Life Society of SA invited Greg along to our April General Meeting to

give a presentation about marine worms and to help us with identification of

some of the worm slides in our Photographic Index of SA Marine Life. He agreed

to come along to talk to us.

Greg started his

presentation off by showing us a video of spawning cuttlefish at Whyalla. At

the end of the video he proceeded with his prepared talk on marine worms. He

discussed, for example, polychaete worms (Phylum Annelida). He said that polychaetes

used to be divided into two Orders – Errantia and Sedentaria. Polychaete worms were

arranged into these two groups according to whether they are ‘free-wandering’ (Errantia) or they are modified for a permanent life in

tubes or sand-burrows (Sedentaria).

(I later asked

Greg about this and he directed me to

http://tolweb.org/tree?group=Annelida&contgroup=Bilateria

which included comments about ‘Errantia’

and ‘Sedentaria’. I have kept a file copy of the web

page. More about this later.)

Greg’s talk in

was illustrated by the use of a digital projector. He went on to say that

(world-wide) there are more than 9,000 species of polychaete

worms.

(This is also

explained on the web page at

http://tolweb.org/tree?group=Annelida&contgroup=Bilateria

where it says “Around 9000 species of polychaetes

are currently recognized with several thousand more names in synonymy, and the

overall systematics of the group remains unstable.”)

Greg then told

us of two surveys that had been done under the Edithburgh jetty on SA’s Yorke

Peninsula. Myzostome worms and their crinoid (feather-stars) hosts were discussed, including

stalked crinoids (or sea lilies). He told us about the recent naming of two new

worm species – Myzostoma australe and Myzostoma

seymourcollegiorum.

(The naming of

these two Myzostoma worms was reported in our

February 2004 Newsletter (No.307) in the article titled “New Bluff Resident

Discovered”. Greg discovered Myzostoma australe, however, in the waters of the Nuyts

Archipelago near Ceduna during the Encounter 2002 Expedition to the Isles of St

Francis. It was Myzostoma seymourcollegiorum that he found in Encounter Bay,

Victor Harbor (at the Bluff) in 2003. More about this later.)

Greg told us

about the SA Museum’s marine photographic index which can be viewed at

http://129.127.105.50:591/index.html

(At the time of

writing, the site is undergoing rebuilding but it should be up again soon.) He

then went on to tell us about the discovery of two new species of worms found

living on the bones of a 9-10m long dead Gray Whale, Eschrichtius

robustus. (I later found some details about these

two new species of worms on the Internet. More details about this follow

shortly.)

At the end of

Greg’s presentation he was able to help us to identify some of the worm slides in

our Photo Index. This allowed us to tidy up the details of worms in our Photo

Index a little bit.

Now, here is my

version of some details that I found on the Internet about the discovery of the

two new species of worms found living on the bones of a dead Gray Whale: -

Researchers from

the Monterey Bay Aquarium and Research Institute were studying clam ecology

when they made the discovery. They found the first of the worms on 8th

February 2002. They were using a remotely operated submarine (called Tiburon,

after the Spanish for shark) which discovered the Gray Whale carcass at a depth

of 2,891m in the Monterey Canyon (Monterey Bay, California).

When they got

the whale rib bone to the surface, they immediately knew that they were dealing

with something totally different. At first, the researchers were at a loss to

determine what kind of creature they had found.

Further remotely

operated submarine dives were made to collect more specimens of worms from the

same Gray Whale carcass. A piece of vertebra and another rib were both

collected on 7th August 2002.

Two species of

worm were found on the whale carcass. These worms were quite strange in that

they had neither eyes or a stomach, and not even any mouth. The worms range in

size from 25 to 63mm long. They have colourful, feathery plumes that serve as

gills. They also have green ‘roots’ that work their way into the bones of dead

whales. Bacteria living in the worms digest the fats and oils in the whalebone.

The researchers named the worms, a new genus, Osedax,

which is Latin for ‘bone eating’.

Researcher Dr

Robert Vrijenhoek said “The worms provide insight

into the cycling of carbon that reaches the bottom of the ocean. A dead whale

delivers the equivalent of 2000 years of 'marine snow' drifting to the bottom

where carbon is fixed into organic molecules. Marine snow is made up of bits of

dead fish and other matter that settle to the floor of the sea, feeding many

creatures there. The worms turn whalebone fats into worm eggs and larvae that

are carried away from the carcass to produce new worms (or to be eaten and

dispersed by other animals). This discovery adds to the limited knowledge we

have about what happens to organic carbon on the bottom of the ocean”.

The researchers

were puzzled when all of the worms were found to be female. Greg Rouse took

some to his laboratory for study and discovered tiny male worms living inside

the tubes of females. There were up to100 or more males with each female.

Photograph of one of the dissected Osedax worms (courtesy of Greg Rouse).

Bacteria are found in the green tissue and part of it has been torn,

exposing the white ovary.

The males still

contained bits of yolk, as if they had never developed past their larval stage,

but they also contained large amounts of sperm. The female worms, regardless of

size, were full of eggs.

Dr Vrijenhoek said that a whale carcass might last for decades

before it is fully consumed. The carcasses (‘whale fall’) tend to be found

along migration routes so that eggs dispersed from one whale-eating worm may

find another carcass nearby. He also said that the worms have no mouth, no

guts, no obvious segments like all worms are supposed

to have.

He said that

they look very much like little miniature versions of the strange worms

discovered living around hydrothermal vents in the oceans. These vents are

cracks in the ocean floor where very hot, mineral-rich water bubbles out from

the earth's crust. When the team extracted DNA from the new worms they

discovered that they were indeed related to the giant vent worms. The vent

worms have colonies of bacteria allowing them to live off sulphides

released from the vents, while the new worms have bacteria that digest fats

from bones.

The new

whalebone worms were divided into two species, Osedax

rubiplumus (for their red feathery gills) and O.

frankpressi (in honor of Frank Press). Frank is a

former President of the National Academy of Sciences who recently retired from

the board of the Monterey Bay Aquarium and Research Institute.

The researchers

concluded that the most recent common ancestor of the worms lived roughly 42m

years ago, about the same time whales themselves first evolved. This is all

explained in the paper “Osedax: Bone-eating

Marine Worms with Dwarf Males” by GW Rouse, SK Goffredi

& RC Vrijenhoek (under “Molecular-clock

calibration”). A copy of this paper is now being held in the MLSSA library.

Paratypes of both worm species are being held at both the Los

Angeles County Museum and the South Australian Museum. Additional material is

being held by the Monterey Bay Aquarium and Research Institute and as

histological slides at the SA Museum.

The Osedax worm research was funded by the David and

Lucille Packard Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the South

Australian Museum.

I asked Greg for

the full classification details for Osedax. He told me “Osedax

is in the group (more inclusive as you go along) Siboglinidae,

Sabellida, Canalipalpata, Annelida. The group Siboglinidae

used to be outside Annelida and was actually two

separate phyla, Pogonophora and Vestimentifera.

Some of my research showed that these two groups belonged together and inside Annelida. The name changed back to the first group name

which was Siboglinidae from 1914”.

Greg Rouse

participated in the “Encounter 2002” scientific expedition to the Isles of St

Francis in the Nuyts Archipelago in the Great Australian Bight (SA). He joined

some of our state’s leading botanists, marine biologists and archaeologists

including Dr Sue Murray-Jones and Dr Scoresby Shepherd (our Patron). The team

of 28 scientists went on board the RV Ngerin

for the 11-day expedition in February 2002.

My article “My

Continuing “Encounter” Experiences” in our 2004 MLSSA Journal reported that the

scientists “discovered eight new species of jellyfish. The results of the

expedition were released in the “South Australian Geographical Journal”, the

Journal of the Royal Society of South Australia. These (jellyfish) details were

reported in our February 2004 Newsletter (No.307)” (following the report about

Greg Rouse’s Myzostoma

worms).

Greg’s discovery

of Myzostoma australe

was also reported in the “South Australian Geographical Journal”, the Journal

of the Royal Society of South Australia. His description is reported in the

article “Encounter 2002 Expedition to the Isles of St Francis, South Australia:

Myzostoma australe

(Myzostomida), A new crinoid

associated worm from South Australia” in the “Transactions of the Royal Society

of S.Aust (2003).

In his opening

summary, Greg wrote that “No Myzostomida have been described from southern Australian waters. Most of

the described myzostome taxa

to date have been found in the warmer waters of the Indo-Pacific, where their crinoid hosts are most diverse. In this paper a new myzostome, Myzostoma australe n.sp., is described from the crinoid Ptilometra macronema

(Muller 1846) (Ptilometridae) taken from waters off

the Nuyts Archipelago, near Ceduna, South Australia”.

He went on to

say that “Myzostoma australe

is an ectocommensal on P. macronema

and somewhat resembles other Myzostoma informally

placed as the ‘ambiguum’ group by Grygier (1990). It differs from these in having a markedly

ellipsoidal body with an oval arrangement of parapodia

displaced forward, combined with the anterior two pairs and posterior pair of

cirri being longer than the rest. There has previously been no myzostome recorded from any species of Ptilometra”.

More details about Ptilometra macronema later.

Greg’s article

went on to describe Myzostomida in the Introduction

and the numbers of species recorded from around the Australian coast. Myzostome expert Mark J Grygier

indicated one species of myzostome from SA waters but

did not describe or name it. He had indicated in 1990 that his myzostome species (No.37) occurs on the comasterid

crinoid Cenolia trichoptera (Muller, 1846).

(This ends Part 1 - The second part will

be in the January Newsletter)