Marine Life Society of South Australia Inc.

Newsletter

October 2004

No. 315"understanding, enjoying & caring for our oceans"

Next Meeting

Our October General meeting will be held at the Conservation Centre, 120 Wakefield Street, Adelaide on Wednesday 20th commencing at 7.30pm.

Our speaker will be MLSSA member Kevin Smith. He will be discussing Pipefish.

PARKING

Please remember – there is NO parking down the side lane. This is now a tow-away area.

Contents

2005 Calendar

Ghost Sharks

Ningaloo Reef Snorkel

Contributors

This month our authors are Steve Reynolds and Philip Hall.

Friends of Gulf St Vincent Honorary Membership

A reciprocal Honorary Membership was agreed with

Friends of Gulf St Vincent at our September General Meeting. This will need to be reconfirmed each September as our Constitution only allows for a one year term as Honorary Member.

The 2005 Calendar is now available from Committee Members, at meetings, by phoning 08 8294 7273 or 08 8270 4463

or by email either at

marinelifesa@chariot.net.au

or

pmhall@chariot.net.au

They cost AUS$10.00 a copy for non-members with a discount to AUS $8.00 a copy with a bulk order for 20 or more placed at the same time.

Member cost is AUS $8.00 a copy.

by Steve Reynolds

Firstly, all fish, including sharks, belong to the phylum Chordata (all animals with backbones). Fish then belong to the Subphylum Craniata. This covers all Chordates that have skulls. "Biological Science – the web of life (Part 1)", however, uses ‘Vertebrata’ in place of Craniata.

Craniata has two main Classes, Agnatha and Gnathostomata. Agnatha covers species where the lower jaw is absent. Gnathostomata covers species where the lower jaw is present.

Gnathostomata has three or four Subclasses, depending on your source of information. The main three Subclasses are Teleostomi (bony fishes), Elasmobranchii (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (Ghost Sharks).

Some references put skates and rays into a Subclass of their own (Batoidea) but others include them with the sharks (Elasmobranchii).

I checked out Elasmobranch taxonomy through the Internet when I visited http://www.elasmodiver.com/elasmobranch_taxonomy.htm . This web page put sharks, skates and rays together under the Subclass Elasmobranchii. It also gave the following taxonomic details: -

Elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays): –

Phylum Chordata

Subphylum Vertebrata

Class Chondrichthyes*

Subclass Elasmobranchii.

*It said "Class Chondrichthyes (is) Cartilaginous fishes lacking true bone". (Chondrichthyes is Greek for ‘cartilaginous fish’. ‘Chondros’ means cartilage and ‘ichthyes’ means fish.)

It also said "Chondrichthyes can be split into two distinct Subclasses – Elasmobranchii and Bradyodonti". I don’t know what became of Subclass Holocephali. It now seems to have been replaced by Bradyodonti. The elasmodiver taxonomy site indicates that Ghost Sharks are now in the Subclass Bradyodonti.

Most sharks are placed into a Superorder called Selachoidei. This Super Order covers many Orders (and Family) of sharks. This group (Selachii) includes sharks, dogfish, skates and rays. It is just the Ghost Sharks that are in a separate Subclass of their own, Bradyodonti or Holocephali. These include the Ghost Sharks and Elephant-fishes (or Rat-tails as they are popularly named).

I have attempted to set out the above details in table form.

See Table 1 below: -

Table 1:

Phylum Chordata

|

Subphylum |

Class |

Superorder |

Subclass |

|

Craniata (or Vertebrata) |

Agnatha (lower jaw absent) |

1.Petromyzones (Lampreys) 2.Myxini (Hagfishes) | |

|

" |

Gnathostomata (lower jaw present) |

||

|

" |

Chondrichthyes (Cartilaginous fishes) |

Selachoidei (Selachii) |

1.Elasmobranchii (typical sharks) |

|

" |

" |

" |

2.Batoidea(skates & rays) |

|

" |

" |

3.Bradyodonti (or Holocephali) (Ghost Sharks) | |

|

" |

Osteichthyes (Bony fishes) |

*Actinopterygii & Crossopterygii |

4.Teleostomi (bony fishes) |

* Crossopterygii is made up of just ancient fish species. Actinopterygii is made up of modern fish species. Then there are ‘Infra-class’ such as Holostei, Teleostei and Chondrostei! And then there are several ‘Superorders’, Orders, Suborders and Families!

Ghost Sharks are also known as Chimaeras because they belong to the Order Chimaeriformes. The "Elasmodiver" taxonomy web page says that the Subclass Bradyodonti comprises the Order Chimaeriformes (Chimaeras). It also says that Bradyodonti "includes forms with an upper jaw fused to the braincase and a flap of skin, the operculum covering the gill slits. Bradyodonti includes the chimaeras and ratfishes, which are relatively rare, often deep-water, mollusc-eating forms".

Chimaeras lack the shark’s skin denticles and their tail fins are extended into a whip-like cord. They live deep in the oceans and are bottom feeders like the rays. They first appeared about 180m years ago (in the lower Jurassic period of geological time). Their ancestors possibly existed more than 200m years ago (during the Triassic period).

I found the following information about "Chimera" through the Internet at http://www.seafriends.org.nz/enviro/fish/sharkray/chimera.htm

and http://www.eaudrey.com/myth/chimera.htm

:-"Khimaira" is Greek for "female goat". In Greek mythology, a Chimera is either "a fire-breathing female monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body and a serpent’s tail" or a "Monster with three heads – a goat, a lion, and a dragon (or serpent) for a tail. The Chimera supposedly breathed fire". This female monster was killed by Bellerophon, with the help of Pegasus. A drawing of Bellerophon, Pegasus and the Chimaera is featured on the web page at http://www.eaudrey.com/myth/chimera.htm .

According to "The Marine and Freshwater Fishes of South Australia (second edition)" (TM&FFSA), there are two families of South Australian Chimaeriformes (Chimaeridae and Callorhynchidae). The Spookfish, Hydrolagus ogilbyi belong to the family Chimaeridae. The Elephant Shark (or Elephant Fish), Callorhynchus milii belongs to the family Callorhynchidae. See Table 2 below: -

Table 2:

Chondrichthyes (Cartilaginous fish)

|

Subclass |

Superorder |

Order |

Families |

|

Elasmobranchii (typ.sharks) |

Selachoidei |

several |

several |

|

Batoidea (skates & rays) |

Booted |

several |

several |

|

Bradyodonti (or Holocephali) (Ghost Sharks) |

- |

Chimaeriformes |

Chimaeridae & Callorhynchidae |

Elephant Fish are apparently also found off New Zealand. Three species of Ghost Shark also occur there.

According to TM&FFSA, "Holocephali fish first appeared about 180m years ago as fossils in the lower Jurassic period of geological time". The book goes on to say that "The skeleton is composed almost entirely of cartilage, some of which may become partly calcified". So Ghost Sharks are related to sharks because they are midway between soft and hard-boned fishes. TM&FFSA says that Holocephali also have other definite shark-like affinities but other things entitle them to be separated from the sharks. It says, for example, that they have just a single gill opening on each side, large goggly eyes and faintly luminescent bodies.

"A Dictionary of Biology" says that Holocephali have large flat crushing teeth and that they are also palatoquadrate (fusion of the upper jaw to the skull). Selachii, on the other hand, have sharp, rapidly replaced teeth and an upper jaw not fused to the skull.

The large flat crushing teeth and the fusion of the upper jaw to the skull in Holcephali are said to be associated with a diet of molluscs. The dictionary also says that Holocephali have an operculum covering the gill slits.

Instead of a penis, male sharks (and Ghost Sharks) have pterygopodes (or claspers), which are used in copulation with females. Male sharks and rays have two claspers which are rod-like structures attached to the ventral fin. They are normally formed from the pelvic fins of males. It is only necessary for one of these claspers to enter the female’s cloaca for insemination (fertilization of her eggs) to take place. Grooves along each of the claspers transfer sperm to the female’s cloaca and, ultimately, to her oviduct.

The web page at http://www.seafriends.org.nz/enviro/fish/sharkray/chimaeri.htm refers to claspers as "intromittent sexual organs". This just means "the male organ used in copulation".

An Elephant Shark egg case, loaned by the Star of the Sea Marine Discovery

Centre, photographed on Henley Beach by Philip Hall.

Male Ghost Sharks, however, have extra claspers. One of these is mysteriously located on the top of the head (in the shape of a spiked club). The Seafriends web page refers to it as a ‘club-like frontal clasper’. Its use is unknown. Extra claspers are located in front of the normal two claspers on the abdomen. The Seafriends web page says that this second pair of claspers is flat and retractable. It also says "These are usually armed with hooks and are probably used only to grip the female during mating".

Fertilisation is internal and all species are oviparous (egg layers). The Seafriends web page says that Chimaerids lay "large eggs in a horny case which is deposited on the bottom". It also says that "development is slow and the young do not hatch until six months to a year after the eggs are laid".

A photograph of a Ghost Shark egg case is featured on page 21 of TM&FFSA. The caption says that they are "often found on the beach after storms".

A drawing of an Elephant Shark/Fish egg case is featured on the Seafriends "Chimaerids" web page. The relevant text (under "Life history") says "the females lay large eggs contained in a yellow-brown horny capsule . . . measuring about 25x10 cm, and which looks like a piece of seaweed. In the centre of the egg case is a cavity in which the embryo develops. From one end of this cavity a passage, closed by a special valve, leads to the exterior, and it is through this passage that the young fish, in due course, escapes. The young hatch 6-8 months later (April) and, as with most sharks, are slow growing, taking about 5 years to reach maturity".

There apparently is a beach in New Zealand where large numbers of discarded Elephant Shark/Fish egg cases are frequently washed ashore.

The claspers on the Spookfish, Hydrolagus ogilbyi are said to be ‘trifid’ which I presume refers to the three groups of claspers. "Tricuspid" (for example) means "with three points".

Spookfish are a deep-water species that are found in the Great Australian Bight and Bass Strait. According to TM&FFSA they reach a length of about 85cm. I have, however, a poster titled "Freaks of the Deep" from the Sunday Mail of 22nd May 1994, which says that a pictured Spook fish (sic) was 1.2m long. Much of this length may be in the fish’s tail fin, which is said to be extended into a whip-like cord. The poster went on to say that these fish crush hard-shelled prey at depths of 550-2600m. It is apparently commonly found off Portland (Victoria?) at depths of 600m.

"Australia’s Underwater Wilderness" by Roland Hughes features a photograph of a dead "spook fish" on page 213. The caption for the photo says "The spook fish lives between six hundred and two thousand metres depth and grows to a little over a metre in length".

A drawing of the Spookfish by TC Roughly can be seen on page 62 of TM&FFSA and (as a Ghost Shark) on page 88 of the "Encyclopedia of Australian Fishing, Part 2" (Bay Books, 1979). Drawings by Ayling & Cox of the three species of Ghost Shark found off New Zealand can be seen on the Seafriends "Chimaerids" web page.

Elephant Shark males have a single, curious, club-shaped clasper covered with small spikes on the front of their heads. It is depressible into a cavity in the head. The males also have a pair of leg-like claspers on their abdomens.

The trunk-like proboscis (fleshy skin flap) on the snout of the Elephant Shark should not be confused with claspers. It is used for finding food in the muddy bottoms of deep water.

The single gill slits of the Elephant Shark are concealed under an operculum (flap) which has a dark spot on it. The colour of the body is iridescent silver and is faintly luminescent. "Sea Fishes of Southern Australia" says that the spine in the first dorsal fin is reputed to be venomous.

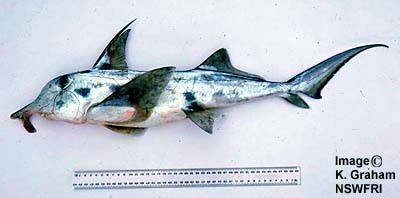

Elephant Sharks inhabit the deep offshore waters of southern Australia but they apparently venture into shallow bays in summer to breed. They reach a length of 1.1m.

Pictures of Elephant Shark can be seen on page 63 of TM&FFSA and page 29 of "Sea Fishes of Southern Australia". One can also be seen on the Seafriends "Chimaerids" web page.This web page gives some good information about Chimaerids i.e. they are ‘hardnosed fishes’.

As mentioned earlier, the Elephant Shark’s scientific name is Callorhynchus milii and it belongs to the family Callorhynchidae. ‘Callosus’ is Latin for ‘hardened skin’ and ‘rhinos’ is Greek for ‘nose’.

Juvenile Elephant Shark hatched and photographed in the

Marine Discovery Centre aquarium at the

Star of the Sea School, Henley Beach.

Photograph by

Ursula Quack-Weatherly

The Seafriends web page also says that "Chimaerids have smooth skins without the dermal denticles of sharks. They also have a single spine in front of their first dorsal fins, which can be laid flat as in bony fishes. Their heads are grooved with lateral lines and their upper jaws are fully fused to their head, unlike in sharks where the upper jaw is only loosely attached to the skull. Their teeth are modified to form flattened crushing plates with sharp cutting margins; two pair in the upper jaw, and a single pair in the lower jaw".

It also says that "Chimaerids live mainly on soft muddy bottoms on the deeper parts of the continental shelf or on the continental slope. They feed mainly on shellfish and bottom-living invertebrates, as well as a few small fish".

Brazilian scientists recently found a kind of fish from the Order Chimaeriformes that is said to have been in the seas since dinosaurs walked the earth. They are referring to it as a ratfish. The ratfish is 30-40cm long and has large wing-like fins. It also has exposed nerves that help it to navigate in the dark.

This picture is courtesy of the Australian Museum and to be found on their website at:

http://www.amonline.net.au/fishes/fishfacts/images/cmilii2.jpg

REFERENCES:

Some of the references used in compiling the above details include: -

"A Dictionary of Biology" by Abercrombie, Hickman & Johnson, Penguin Reference Books, 1964.

"The Marine and Freshwater Fishes of South Australia" by Scott, Glover & Southcott, Govt. Printer SA, 1974 (mlssa No.1008).

"The Jaws of Death" by Xavier Maniguet, Harper Collins Publishers Ltd, 2003.

"Biological Science – the web of life (Part one)", Australian Academy of Science, 1981.

"Joy of Knowledge (Part two)", Rigby International Ltd, 1981.

"Sharks – Australia, the Indo-Pacific and Asia" by Kelvin Aitken, Sport Diving Magazine special feature, 1998 (mlssa No.2132).

"Sharks & other predatory fish of Australia" by Peter Goadby, Jacaranda Pocket Guides, 1963 (mlssa No.1046).

"Encyclopedia of Australian Fishing, Part 2", Bay Books, 1979.

"Australia’s Underwater Wilderness" by Roland Hughes, Weldons P/L, 1985.

"Sea Fishes of Southern Australia" by Barry Hutchins & Roger Swainston, Swainston Publishing, 1986.

WEB SITES

http://www.elasmodiver.com/elasmobranch_taxonomy.htm

http://www.seafriends.org.nz/enviro/fish/sharkray/chimaeri.htm

http://www.eaudrey.com/myth/chimera.htm

by Philip Hall

Pictures by Philip Hall

In June Margaret and I hired a Mobile Home in Perth and made our way up the West Coast. On the way we visited Coral Bay which is approximately at the start of the Ningaloo Reef and here we toured the reef in a glass-bottomed boat and then I snorkelled over it. I began snorkelling slowly as I had not done any for nearly three years. No wetsuit was needed as the Leeuwin Current keeps the water temperature at a warm 25°C. I found the coral was very broken and the fish life to be diverse and reasonably abundant. The visibility was 10 metres or more.

We went further North and stayed at Exmouth. Here we went into the Cape Range National Park on two successive days. We were able to visit Turquoise Bay near the top end of the Ningaloo reef. The weather was perfect with a slight cooling breeze (air temperature was about 30°C) and a brilliantly clear turquoise sea. In the distance, about 2 km away, huge waves were breaking over the outer reef, but where we stood the sea was flat calm.

Turquoise Beach noticeboard. Image adjusted to show the snorkelling area.

For snorkelling the system here is brilliant. You walk south along the beach for about 100 metres. Bathers on. Then you slip on a tee shirt to ward off the sun and sunscreen on any exposed areas. Again the Leeuwin Current keeps the sea at about 26°C so a wetsuit is not necessary.

You only have to wade, then swim, about ten metres towards the reef before you stop swimming and just float in about 2 metres of water, the North Bound Current does all the work for you. The drift along the beach ends about 300 - 400 metres later at a sand spit. It is essential not to miss this or a rip will take you out through a gap in the outer reef and out to sea - something most people want to avoid!

I first waded out and put on fins and my own mask which I had brought with me from home. I then snorkelled a further 5 metres until over the first bommies. For the next 20 minutes I slowly moved over the reef system watching a myriad of colourful fish and sea cucumbers, invertebrates but very little weed. The visibility was much better than at Coral Bay, maybe 20-30 metres.

Snorkellers entering the water.

The outer reef is in the distance.

Once I reached the sand spit I found the current was raging along faster than people on the beach could walk. I staggered out with sand filled bathers but feeling a great exhilaration at the experience. Then I walked back up the beach to where I first entered the water. Back in and I swam just a little further out and drifted again. One little black fish became very aggressive when I flooded my mask and held onto a bommie whilst I cleared it. I had put my hand too close to his wife and territory! Beautiful blue striped rays were burying themselves in the sand whilst other fish swam round picking at the creatures they disturbed. Soon I was back on the sandspit. I carried on over two days to explore and wonder at the marvels of this pristine reef system.